Photo courtesy of Bob Stafford. Photo courtesy of Bob Stafford.

Sometimes in an improv show we find ourselves in a bad scene. How on earth do we deal with that?

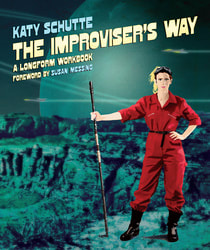

Trust that your team will edit you. They should know you well enough to feel when you’re uncomfortable, or when the scene isn’t working that well. They will edit the scene, just like you would do for them. Stick With It Okay, so no one edited you. Shit. Ah, man, now you’re up in your head. What do you do? The first thing is, don’t edit yourself. It can be very tempting, but it will look like you are bailing on the scene (which you are). By making an excuse to leave as your character, you are leaving the other actor(s) high and dry. By editing the scene itself from inside, you are not trusting your team to edit at a good time. We have other people edit because we are bad judges of the scene we are in. There’s a lot going on in our heads, so it’s best to let the rest of the crew take care of that while you stay present in the scene. Eye Contact So no one’s editing you and it’s bad practice to edit yourself. It doesn’t help being up in your head, but since you’re there already, let’s use your brains to help you. Your scene partner has everything you need. Look them in the eye. What is the emotion that’s coming across? How do they feel about you? It may be that we’re both thinking ahead and forgot to connect. We can build this show together. What You Just Said is Very Important to Me Because… Listen to the last thing your partner said. What were the exact words? Why is that important? Forget the rest of the scene for now, what did they just say? Now decide why that’s so important to your character. Why is this thing so important to me? It works for any line. If they say “Peanuts are shitty” what they just said is very important to you because you also think peanuts are shitty and the amount you have in common suggests they would be a great life-partner. Have an Emotional Reaction It’s great saying that something is important to you, but the best way to telegraph it, is to have an emotional reaction. If knowing your relationship is going really well makes you feel good, show that. It also helps your scene partner react off of you. Say What You’re Thinking Can’t decide on an emotional reaction? Say exactly what’s happening in your head right now. “I can’t do this” “Why is no one helping me?” “I can’t wait till this is over” “What’s wrong with me, I could do this yesterday” These are all really great offers for your co-pilot. Don’t break the fourth wall by commentating on the scene: “This scene is shit”. Say how you feel as if it was happening to this character in this moment. “I feel like I’ve forgotten how to do this”. It helps you be authentic while also giving your fellow improviser something to play with. Build a Platform If you’re feeling lost, see if there’s anything that hasn’t been defined. Knowing what your relationship is to the other player(s), where you are and what’s going on is really helpful. You don’t always have to do these things in the first few lines, but if you’re unsure, setting up the pieces will help you play the scene. Slow Down Some shows can get very information heavy with full and complicated plots and/or lots of characters. Sometimes I will fall behind. If you don’t quite know what’s going on in the show or in the scene you’re in, take a second. Some people’s coping mechanism with a fast paced, complicated show is to add more information. If you’re talking over one another, trying to solve a story by putting more facts in there or adding something different because you don’t want to contradict what’s already happened, just breathe. You don’t have to be talking all the time. So, Let me Just Get This Straight… If you’re not sure what’s going on, there’s a good chance that at least some of your fellow players and the audience will be lost too. Try saying ‘so, let me just get this straight’ and outline what’s going on as best you can. You will clarify what it is for yourself, your team and the audience. If you’ve massively misunderstood something, great; you’ll probably get a laugh and someone will fill you in with the ‘correct’ information or justify your mistake. Use Your Environment What if the problem is that nothing is happening? What if you’re just a rabbit staring into the headlights of the audience? What if no one joined you on stage yet? Discover your environment. Perhaps you know where you are and perhaps you don’t. If you don’t, make a decision. It doesn’t matter where you decide to be; make that decision and stick to it. Now reach out and touch something that would likely be in that environment and use it. How You Do What You Do is Who You Are The way you use objects and environment gives you clues about your character and emotional state. You picked up an apple. Did you peel it with a knife, did you break it in half with your bare hands (my Mum used to do that) or did you bite into it? What are the clues you get from these decisions? Are you aggressive, are you smug, are you considered? Whatever it is, use it to form your character and emotional choice for this scene. Don’t Drop Your Shit Great. You know what’s going on, you have made a connection with your partner, you’ve made a character and emotional choice. Now stick with it. You don’t have to keep thinking about whether or not they were good choices, you just have to double down on them. Escalate the shit out of them. Be Changed But… if your scene partner offers you something that might change your outlook or your emotional state, use it. It’s a great gift. Allow your peanut-loving old man to fall in love, despite his reservations and his penchant for carrying an apple knife. Now They Edit You And you feel pretty good about it. Thanks for reading! Katy Schutte is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes. I have written an improv workbook that will be coming out later this year. Join my mailing list for updates!

377 Comments

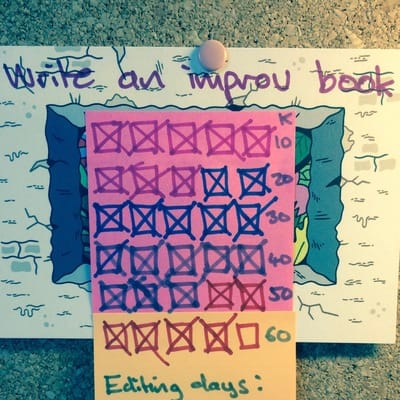

It’s nice to have a round-up, we’ve all done so much more than we think we have! It’s also interesting to notice that some of the big things, the super-highlights are sometimes just things that come along easily and some of the work that is hard-won perhaps isn’t. Next year will be something else; but let’s just enjoy the good stuff from 2016 real quick… 2016 is the first year I’ve been brave enough to be solely an improviser/actor. I performed over 150 shows and taught improv to about 2040 people. Highlights:

Thanks to all my students, friends, loved ones and everyone! And also a big thanks to all my teachers this year:

Bill Arnett, Joe Bill, Michael J Gellman, Jorin Garguilo, Rich Sohn, Mick Napier, Adal Rifai, Farrell Walsh, Bill Arnett, Tj Jagodowski, Rebecca Sohn, Brian Jim O'Connell, Kristen Schier, Mike Descoteaux, Mark Johnson, Kevin Scott, Tim Sniffen, Bina Martin, Shenoah Allen & Craig Cackowski.  Earlier this year, a friend asked me where my blog on alcohol and improv was. I hadn’t yet written one. He felt like it was an essential question to cover as some of his troupe were ‘boozing before shows’ and ‘coming to rehearsal with a four pack’. So - many months too late, but maybe a little more timely because of the festive period - here are my thoughts on drinking and improv. For me personally, I don’t drink before I improvise. But unlike me, the majority of people aren’t doing improv as a career choice. For me, every show I play is a showcase (often to students) and can lead to teaching, coaching, directing or corporate sessions. I want to do my best work every time. I need my brain and to drink anything will take my skill level down. It might lower my inhibitions, but I’m in a place where I’m confident enough on stage that my inhibitions are pretty darn low anyways. Some people drink to help with the nerves. The thing is, if you always drink to deal with your nerves, your sober nerves aren’t going to get any better, you’re just going to build a dependency for drinking alcohol before every show. That might even increase over time when the gigs get bigger and scarier. Also, if you get rid of the nerves before a gig, you are probably putting a damper on the high you will get afterwards. For the majority of improvisers, improv is one of their chosen activities for downtime with their friends, where alcohol (in Britain anyways) is traditionally part of our culture. I’ll have a few beers when I’m playing board games or D&D (Nerd), so I can see why it seems to fit with a night of rehearsals or a low-pressure show. However, neither me or my friends care whether I’m good at board games and no one is paying to watch me play. You’re an adult (probably), so you can make your own decisions, but know that your choices around alcohol will affect the people you play with on stage and your relationships with them off stage. If you’re slower and less physically aware, you make the other players work harder to support you and it stops being an even ensemble. If you’re a solo improviser, I guess it’s truly your decision. The audience is the other player for you. As a group player, there’s also the simple fact that it’s gross playing with someone who reeks of booze. This all sounds a little preachy so far, so sorry about that. I confess that there are a couple of occasions where I do drink before (and sometimes during) improv. The first is New Years Eve. For the last few years, I’ve joined the Hoopla NYE party at the Miller in London Bridge. Lots of improvisers get really drunk and do a bunch of shows. It is ticketed for the public, but only nerdy improvisers go (and a few suffering partners). Because everyone is drunk, most of the improv is pretty self-indulgent. I find that when I’m plastered, the first thing to go is my spatial awareness; I crash into people when I’m editing or edited and I miss a lot of offers that aren’t happening directly in front of me. Also, I slur, so that means any verbal offers I make are hard for other people to understand. I believe at the time that I’m the funniest person in the room, even though I can’t hang onto a character or stop clowning around and breaking the believability of the scene. Once in a while and to an in-crowd, I think self-indulgent nonsense is pretty fun, especially when everyone is so pissed that we’re all in the same boat. The other instance in which I drink is in the Living Room format. I do it because it was taught to me as a bunch of mates on their sofa drinking beers, jumping up and doing improv whenever they are inspired. Beers are for me a part of the form. It might lead us to play around a little more casually, to pretend like we are literally at home and enjoying one another honestly as we would do off stage. Even though I’m drinking beer, I don’t drink before the show and the Corona that I’ll take on with me won’t really hit until towards the end. So really, I’m cheating. I’m having it there as a prop and it won’t hamper what I’m saying or doing. Hopefully it makes our guests relax and know that it’s a casual (often late-night) show. There are other formats where drinking is a part of the entertainment factor of the show. Where one character is drinking throughout and the others are taking care of them, or there are ‘live’ drinks on stage for a genre show, or there are challenges or bits where alcohol is built into the show. I’m fine with those as long as it’s mutually agreed and the audience knows that that is part of the gig. If someone is paying to see improv, they want to see the best show they can. If alcohol adds to the gimmick of the show and all of the performers are in agreement and enjoy that; cool. I’d be happy in the drinking role if I knew people had my back and I’d be happy to babysit if I knew that we got to swap around sometimes. There are veteran improvisers that I’ve seen drink a lot before a show and maybe even get plastered all the way through a 30-50 hour Improvathon and it doesn’t seem to make them bad improvisers. Though I imagine they’d be better if they weren’t hammered. Also, how they hell do they get through an Improvathon whilst drinking? I would be asleep instantly if I drank beer in a 34-hour show. There is no one I regularly work with that gets drunk before performing improv. I have a couple of chums that will have a pint before they go on stage and I’m okay with that. I suggest that a sensible limit is the same as it is for driving. If you can drive a car, you can probably drive yourself and others through an improv show. In jam nights, I would apply the driving limit rules and make that clear to potential performers. People new to improv can be a bit of a liability in terms of boundaries and trust anyway. If it’s a fun night out and we live in a drinking culture, it’s hard to ask people to be totally sober in an unpaid show. If you really want a couple of drinks before a show or rehearsal, it’s good to check in with your group. If it worries anyone that people are drinking beforehand, come to a reasonable compromise so that everyone is happy. As for other substances, I think the above is probably true for those too. Experiment with anything you want if it’s part of the agreed show (depending where you stand on the legality and safety of that substance) and don’t give your fellow improvisers a bunch of work because you’re selfishly indulging. Right. All this talk of beer makes me want a beer. I’m off to get a beer.  I’m really writing this because I’m terrible at watching improv. This is a blog written for me. You can read it if you want, but this is advice from a good me to a bad me. I’m at an improv festival (do I keep saying that?) and I’m watching 4 hours of improv a night. Sometimes I’m a horrible person and I’m just waiting until it’s my show, sometimes, I’m spellbound, sometimes I go into teacher or director head. So how should I watch an improv show? They’re not necessarily my team, but I should still have their backs. Here are some tips for getting better at watching improv. 1.Support When you are playing at a show, please watch the other acts. Yes, you may need to warm up, yes, you may be tired and you’re on first, but think how much you appreciate it when the other groups stay to see you. If you are aware the other groups are very new or not so great, see it as your good deed for the day. If you’ve never heard of them, you should definitely watch them and see what they are up to. If you’ve seen them loads, great, stay and see what’s happening with their show now; improv is different every time, right? Also, you don’t have to awkwardly pretend in the pub that you did see them, or say thank you with no returned compliment. Don’t just sit in the shadows at the back because you’re a performer, there’s no reason you should broadcast that by segregating yourself. Don’t sit in the centre of the front row because that can be intimidating. You shouldn’t be taking up paid punter seats, but you can make a theatre (or a pub room) look more full by filling up the empty seats once everyone else has arrived. Some nights don’t always have enough staff to run the door smoothly (in London anyways) so if people need help finding seats, locating the bathroom or knowing if they have time to get a drink, try and help out. There are sometimes nights in London when technicians, front of house staff and the host haven’t turned up. If you’re comfortable filling a role at the last minute, you should do that. If the night is better, your show will be better. 2.See a Broad Spectrum of Shows Don’t just watch the same group over and over again. It’s all very well me watching Baby Wants Candy every day for several Edinburgh Festivals, but you need to see more than one thing. There are infinite ways of playing and there are a lot of shows and performers out there who can really inspire you. For a few years I thought that I’d seen all of short form, then I took a punt on an American group in Edinburgh and had a really great night. They were slick, funny and I learned a lot of new games. Now I like short form again. You might live nearer to one theatre or another, or have trained at one school. Push yourself to go and see work in other schools and theatres. You never know; their style might be your new favourite. 3.Go See Your Mates Perform I can’t tell you how pleased I am when friends come to see my improv shows. I burned through all my favours in my first two years of stand up, but sometimes muggle chums and improvisers will come to my shows. When I see them there I expect that they’re playing and if they say ‘nah, I just fancied it’ I glow. So give that feeling back. You love improv, remember? So go see your friends in their other shows, see how your fellow students are doing in their new team and be a nice person. A nice person who gets entertained and maybe has a lovely beer. When I watch my co-improvisers perform in other shows, I feel so lucky to play with them. Just last night I watched lots of the Maydays perform in other shows at the BIG IF and I was so thrilled with how excellent they were. What a treat to get to play with those people, I thought. We can take our team buddies for granted, but they’re probably awesome and we’re lucky to have them. 4.Don’t Sit There Looking Like a C**t If you don’t like a show, you really don’t need to broadcast the fact. It doesn’t help anyone, least of all you. You will come across as arrogant or mean or judgy. You don’t have to pretend to laugh, or give a standing ovation just to yes-and the crowd, but it doesn’t help the act for you to sit there with your arms crossed, looking moody. At least look open and encouraging. I’ve certainly been in shows, where I’ve caught the eye of a person who looks like they hate it and it’s made me feel bad. That might even be in a sea of smiles and laughs. I’ve also seen fellow teachers in the audience do ‘edit’ gestures, wince when a performer denies something, point out a reality error like ‘she was a tree, not a human, right?’ (that last one was me). You’re not really checking, you’re showing off that you knew what they missed. Really, you just look like a c**t. Remember that the audience gets 100% of the information that is happening on stage and sometimes performers only get 50% because of where we’re standing and looking. It’s much easier to think of funny bits and clever plots from your comfortable seat in the crowd. 5.Have a Cheeky Workout You can always get more reps in by watching improvisation. It’s another gym trip for your brain. Ideally it would be such a great show that you can just sit there and enjoy the shit out of it without even thinking. Often though we can be exposed to a lot of mediocre work, or in a workshop where we are sitting and watching two person scenes forever but there are necessarily times when we have to sit and watch. Make your watching active. In the audience, learn all the character names like you would on stage, look for when you might edit, think about the themes, get ideas for follow-me scenes or work out the subtext between the characters. Log where objects and scenery are placed, think of how you’d wrap up the story. I’m not saying you should be this in-your-head when you’re playing on stage, but it’s a great way of practising when you’re the audience in class or you’re watching a show. 6.Decide What You Love It was the worst show you’ve ever seen. But what did you love about it? There must have been something? One of the initiations was amazing, that guy was great at object work, the pianist was really good. It’s a given that we dislike improv where people listen poorly to one another and treat each other badly, so let’s get over that and find things we love. Also – did other people like it? Just because you didn’t, that doesn’t mean it’s shit. 7.Pick Something You Can Use A person, a form, a style, an edit; anything you like. Here are some things that inspired me from the shows I watched last night:

8.Only Offer Advice If You’re Asked I’ve had people come up to me immediately after a show and give me notes. Not my director, not a teacher, sometimes a friend (who doesn’t do improv) and sometimes a student of mine. It’s weird, guys. First of all, I don’t want my tiny little high ruined by this person being objective (and objectively negative) about the performance I’ve just given. I’m a pretty destructive critic of myself, so I really don’t need a third person adding to the poo poo party. If you are asked for advice, check if that’s really what they want; do they just need an ego boost or is this really a demand for creative notes? If they want notes, make them general things they can apply to their next show, not things they should have done this time. Also, you’re not obliged to offer free advice. 9.Take Action for Your Show So we’ve learned how not to be neg about everything. But what triggered you because you do it? I think it bugs me when people do a lot of love stories, awkward rom coms and play ditzy American characters because I do too much of that. I’m just retroactively watching myself and saying ‘enough’! So rather than deciding you don’t like that show, see if there’s anything you can change about your work, or the group you work with. 10.Applaud  What is character? Someone asked me this in class and as I went to say the simple answer, I realised I didn’t really have one to hand. Instead, I thought about how different students and performers find their way in to being somebody else. Some of us are outside-in and some of us are inside-out and the audience may not even know the difference, Outside-in: I have taken and given a lot of classes where people are asked to walk around the room imagining that they have a rope pulling them forward from different places on their body. What happens is that it changes your body shape, your rhythm and your way of walking. In IO Chicago they call it Stacking when you move your spine into a different position to alter your stance. None of this is character yet, it is more like a chicken wire mesh that we can build a character on. So you start with a position, then you try speaking with the voice that would ‘suit’ this person. Often, you end up with stooped lower class characters and eyebrow-raised, tall upper class characters. I always found this creation of characters easy and sort of archetypal. An accent or way of speaking will inevitably follow your stance and walk and you will ‘know’ who you are playing even if you can’t articulate it yet. When you’re asked questions like ‘what is your name?’, ‘what do you have in your pocket?’ or ‘what pet do you have?’ you know the answers pretty quickly. Inside-out: Start with discovering your point of view and the character follows. I learned some great point of view stuff from Rich Talarico at the Out of Bounds Comedy Festival in Austin, Texas. After a decade of learning character exercises, this was the only one that really changed and varied my character creation. We played objects in a room. We were just sitting on chairs, so there was no staging or much physicality. By talking to the other objects, we found out what our point of view was in relation to every other object. I was surprised and delighted to discover that this came out organically. It was clunky at first, but soon, I found that it was clear how much the old clock envied the new side table or the fireplace fancied the lamp. Now the BEST PART was handing someone else your role in the scene. We passed them a card that said ‘lamp’ or whatever we were playing, but explained to them who the character was as if they were our understudy. The clearest character explanation ever. It’s not about the text of the scene, you wouldn’t be telling that to your swing in a theatre show, it’s not about the accent or physicality because that’s up to the actor herself. It’s a clear point of view. “You are this lamp that has just been introduced to a room full of older objects; you are really trying to please them and be one of the gang.” It’s not that different than having a secret want or motivation or goal. Now add the above on to this for free; the characterisation bit. Make it like a Pixar character. How would Pixar personify a side table? What voice would this one have? How would it stand or move? So whether you start with the body (outside-in) or in your head with a point of view (inside-out), we get to create a whole character, one piece at a time.  I’ve been asked a handful of times over the last week if I have advice for how to do well in improv castings. I coach, teach and direct improv shows and I’m also an actor, so I know the stresses that can come with auditions. I can’t speak for everyone, but I can tell you what I would be looking for in an improv audition. 1. It starts on the way You never know who you will bump into on your way to the casting, so be in polite and lovely mode the whole time. Make a point of saying hello to other people at the venue and in the waiting room. You want them all to be allies and it might be the only connection you get with your fellow players before you’re put in a scene with them. 2. Be on time Duh! Leave lots of time for disasters en route. Be early. Get a cuppa and walk around the block. Being late is the stupidest reason for not getting a job. Even if it’s the only time you’ve ever been late, they will think you’re generally a late or unreliable person. If you do have a series of disasters that makes you late, try to take a breath before you go in. Don’t be flustered, just apologise and join in with a minimum of fuss. 3. Dress appropriately Make sure you’re wearing something you can move in and something that won’t show off your bits when you do physical work. Scrappy clothes indicate that you don’t care or that you’re super poor because you’ve NEVER got a job EVER (even if that’s the case, you don’t want them to know that). 4. Bring water Some people don’t. Amazing. 5. Support, not showboating Your instinct will be that you want to be seen, to stand out, but if you have a good improviser running the casting, they will notice how good or bad you are at support. Even in auditions, it’s super important to make the other person look good by really listening to them, building on their ideas and editing at a time that serves the scene. How many people are playing? Work out the % you should show up on stage. Don’t hang back or be in every single scene. You don’t need to do every single idea you have, but serve the scene or the set you are performing in. 6. Be a great audience If you are watching other people at any point in the casting, there is nothing nicer than laughing and smiling and caring about the other improv that’s happening. It may feel counter intuitive because you want to get the job, but you’ll look like a nice human that enjoys improv and who doesn’t want that person on their team?! 7. Show your range Just like a good show, you’re going to need variation in your performance. If you’re initiating a lot, make sure you do some scenes where you’re responding and reacting off someone else’s initiation. If you’ve played a lot of big, cartoonish characters thus far, play some real-world characters that are close to you, play honest and truthful over funny. Do talky scenes after doing a lot of quiet scenes and so forth. 8. Do your research Who are these guys? What is their style? Where do they play? What do you like about them? Get ready to answer questions about why you want to be in this group. Also, check in with yourself; is this where you want to be? 9. Be yourself If you’re very adaptable and you can blag your way into a show without it really suiting you and how you like to play, that’s not going to be much fun. Make sure that you make choices because they’re exciting to you, not because you’re trying to prove anything. If you get it, they will be casting you for you and you’ll have a much nicer time. I have found that being myself has got me a lot more work that trying to guess what a casting director wants and trying to please them. However... 10. Take direction Listen out for what you are being asked to do; it sounds simple, but SO many people just can’t take direction. If your director wants you to play in a different way, or try something out, go with it; that’s less decisions you have to make! The director really wants you to be the best. They are not looking for anyone to fail. The best outcome for them is that everyone is brilliant. 11. Be kind to yourself if you don’t get it There are three main reasons for not getting a job

12. Above and beyond You are much more likely to be liked and noticed if the group have seen you at their shows. It indicates that you really enjoy what they do. Go say hi, but don’t hang around them awkwardly! See if you can help on lights or sound or tearing tickets. If going to their shows feels like a chore, it’s probably not a group you really want to be a part of anyway. My favourite advice (I think I learned this from a Brian Cranston video): Auditioning is the whole of the job. You came and you did your best. It’s just a bonus if you actually book the work. Think of it that way and you’ll be satisfied before you even know the result. Bonne chance! Katy Schutte is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes.  Do you laugh while you’re improvising in front of an audience? We also call it corpsing or breaking. Many improvisers break into uncontrollable laughter on stage and some ask me if I have any tips on how to stop it happening. But should we stop corpsing? We laugh for lots of reasons; because something is funny, because it’s a surprise, because we’re scared or because we’re uncomfortable. Sometimes that laughter becomes irrepressible and then we’re into corpsing territory. Improv is the perfect petri dish for this kind of laughter; we’re constantly being funny and surprising and putting ourselves in scary new territory. We have an interesting relationship with laughter in the improv comedy world. The immediate reaction of most people to laughing in a scene (in class) is that they apologise and try and get back to the scene without laughing. I personally think it’s fine to laugh, but it’s all about how you use it. Laugh all you want in short form. The games are a loose, casual way to play around in front of an audience. There are buttons for laughter built into those games and the audience enjoy the Brechtian angle of watching the actors play other characters, look like an idiot, or try and achieve something difficult. Theatre and Comedy Sports also have a third level of watching the actors pretend to compete as well, in which case we enjoy them laughing to show us that the goal is something other than winning. In shows with a fourth wall, laughter can mess up a scene if you let it become corpsing. It takes the audience out of the immersive feel of the show, reminding us that these are performers playing characters. Ergo we care less about the emotional journeys of those characters. But laughing in and of itself is actually not the problem, it’s what you do with it. Say you’re having a scene in which some bad news is imparted. If one of you corpses and then tries – as yourself - to cover it up, you have lost the audience’s belief; but if you treat that as a genuine character reaction; awesome. That’s a cool choice to have made and comes from truth, so can really help create your scene. As well as breaking the dramatic tension of a show, laughter can sometimes feel self indulgent and alienating for the audience. If you faux-corpse, I reckon everyone sees right through it. It reads as a cry for attention and a way of telling us that you aren’t confident enough about your show. Having said that, some people (Baby Wants Candy for one) just get away with it. Some small percentage of performers demonstrate their joy at where they are and what’s happening to such a delightful degree that all the above is forgiven. With those happy few, I can continue to care about the characters, not be annoyed by their smugness at their own performance and actually have a better time. Perhaps the difference is that those people are enjoying the improv of their fellow cast, they’re not worried about the show and that they really are just… laughing. But if you really need it, here are some ways to stop corpsing in your improv show:

And what about being on the other side? What do you do when your scene partner breaks? If someone other than you laughs, double down on your character and react how they would react in that situation. See how much more fun it is than breaking the moment. Committing to that isn’t the boring, ‘supposed to’ route; it is the more fun, deeper end route to making great improv. I see a lot of scenes where improvisers play upset, crying even, but much less where the characters themselves are laughing out loud. What a beautiful gift. Katy Schutte is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes.  Photo courtesy of Mark Dawson Photo courtesy of Mark Dawson I am pretty scared to be publishing this article. I am worried that I am using the wrong terminology, that I will appear naïve, that I will alienate directors and actors that I have implicated and that I will somehow end up gender-casting other people in improv and be a hypocrite. But - in the spirit of our art form - I’m going to take the chance. I am willing to be wrong and my best hope is that I can at least help people to start or continue having this conversation. I hope that in being honest about my opinions, we can have an open discussion about women not just playing women in improv. More and more I hear people say that they have asked the women in their improv show to just play women and the men to just play men. The reasoning is normally ‘to make it more like theatre’. In my experience I have only seen men make this decision. One of the things that I find the most fun and rewarding about being an improviser is that we are not hampered by our casting. By casting, I mean what people assume about you the moment they look at you. That is about age, gender, race and also how you dress. If I go to a casting for a commercial, I’m only ever going to be able to play what I look like. Right now, I’m 36 with a blonde frizzy bob and 50s cat eye Ray Bans. I’m a slightly pear-shaped size 10 with a weak chin currently having my teeth put in a straight line. Recently I have played a School Teacher, a Wife/Mother, the voice in someone’s head, a peasant, a queen, a presenter and an antiques dealer. All of those have been comedy roles because of the quirky girl-next-door comedy face I have. I won’t be cast as American because of my still-working-on-it teeth, I won’t be cast as male because I’m female and I won’t be cast as ages that are much different than my own. Unless or until I become a ‘name’ it’s unlikely I’ll be cast outside of my actual physical appearance on screen. Perhaps because of my casting, one of the things I adore in improv is that I can play anyone. I can change my posture and movement to give the impression of a different body, I can play the beauty, the man, the very old, the very young and any race I dare to play without offending anyone. Also, I can play a lamp if I want to, or a concept, or a farm animal. I once improvised the bridge of a song as a turd floating in a jacuzzi. When we start calling ‘theatre’ an excuse for casting improv a certain way, it makes me sad. There is also a terrible lack of diversity in the London improv scene that I hope we can change. Perhaps someone can speak to that from experience in the same way I can talk about my gender and certainly it’s up to those of us making and casting shows to be inclusive. I dislike the argument that the audience ‘will not understand’ that a man is playing a woman or a woman is playing a man. If you are clear with the names you use, the physicality you adopt and so forth the audience will definitely come with you. The same people that cast shows gender-appropriately, do not often have people play their own age, their own appearance or their own race, so why is gender the one that gets enforced? Play to the top of your intelligence and don’t patronise the audience. If they really don’t get the fact that a man is playing a women the first time, it will be an education and the next time around we will all be smarter. I watched a show recently that was cast with women only playing women and men only playing men. The director is one of my best chums and is a Feminist. It is a show that travels forward through history in one tiny spot of land. As you can imagine, the story contained a lot of incidences of women being repressed throughout civilised culture and the women always played the subordinate, weak roles. This might have been a Feminist commentary, but sadly, every single female interaction always mentioned men, relationships with men and sex with men. There was no scene where women were talking exclusively about anything else for more than a line or two. In the one scene where I did see a woman taking charge of the scene by reframing a witch hunt in favour of the woman, I was sad to see it switched back (and denied) by the man in the scene. I don’t think that casting choice helped the show and actually made the innate sexism of the ages fall back into the present day. As part of Slapdash Festival a few years ago, I took part in a John Hughes improv show that was cast with women only playing women and men only playing men. The men got to be the bike-riding fun-having college teens and the women got to be the girls obsessed with those men. Yes, that is honouring the genre, but I really don’t think it would have been a struggle to play across gender and have the audience come with us. After all, we were all in our 30s and 40s playing teenagers and half of us were Brits playing Americans. My third example is a corporate job I did recently where we enacted The Dream. In this short format, you ask for the real life experiences of an audience member and then show them the dream or nightmare that they might have that night. Before the show there was a debate about who could or should play the audience member. I argued that any one of us that had an idea or felt the urge should step up to play them or it should fall out organically. Others (including the other woman in the cast) felt that the audience wouldn’t be able to cope with the fact that a man might be playing a woman, or a woman a man. I believe that if you use their name in the first instance it’s easy to know who they are and if that’s too hard; they are the protagonist of the story you just heard! Go figure! People aren’t stupid. If they are; educate them. Treat the audience as poets and geniuses. Please let us educate our audiences and our directors. Let’s enjoy the full range of make ‘em ups and be able to play whoever and whatever we please. In improv, I can play a cat, a sunset or a 5 year old, so why can’t I play a man? Thanks for reading. Katy Schutte is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes. Please also take a look at this article by Stephen Davidson (which came out after I’d written this one, but before I published). Stephen asks why gender should come into it as much as it does. Does everything and everyone we play need to be defined in that way? I also enjoyed talking to improviser Christine Brooks about this. She suggests that we should play more women in improv and really work on our characters being rounded, having agency and caring about one-another. Rather than just playing male archetypal roles, let’s spend the time actively celebrating the diverse roles of women and their representations in art. I’m currently coaching this long form for Classic Andy and All Made Up and teaching it as part of my Hoopla advanced class. It’s a nice simple one and fun to play. I wrote this cheat sheet for my students, so I’m hoping it might be useful for others.

I learned the Living Room as part of an IO class in 2013 taught by Charna Halpern. Me and Tony Harris then played our version ‘At Home with Katy and Tony’ at the Hoopla Comedy Club in London Bridge for a few years. The Maydays also perform it at the biannual improv retreat in Dorset. As with any format, things morph and change via different groups and teachers and this is the version I have ended up with. History: Charna tells me that the form comes from long form group The Family. They would chat in Charna’s living room and because they are improvisers, they would jump up and do scenes during their conversations. Charna loved watching them, so she took her living room furniture to IO and asked The Family to improvise on stage exactly like they did in her home, beer-drinking included. Structure: The format itself is very simple. There is a sofa on one side of the stage and an open playing space on the other with a couple of chairs. The form starts with an audience suggestion, the players chat, the players do one scene, the players chat, they do one scene and so forth until the time runs out. It really is one scene at a time and not a run of scenes. Timing: The show can run from 15 minutes up to an hour. If you do an hour, you should really make sure the pace changes, the stories evolve and characters come back. We’ve also played it where we do the show in 2-3 chapters where we switch up our guests. Number of players: In class, we used 5 or 6 players. On stage we sometimes had more. It’s also possible to play the form with more people by allocating the chats to half the players and the scenes to the other half, perhaps with a switch in-between. It’s more fun if you all get to do everything, though. The call-out/ask-for: This is what you get from the audience to begin your show. Me and Tony would ask; ‘What’s the weirdest house-warming/Christmas present you ever received?’, ‘Is there an object in your house you’d like to get rid of, but you can’t?’ or similar. We’d use the suggestion to inspire our conversation. You can ask for anything, though I wouldn’t get a story, because you’re about to do a bunch of chatting. Chats: It’s important that everything you talk about on the sofa is TRUE and that you make that clear to the audience beforehand. It’s generally more interesting if it’s about you personally, rather than you telling a story third hand. Be careful of falling into pop-culture conversations. Amazingly, it’s more interesting to hear about your life and your opinions than it is to discuss what just happened on Game of Thrones. None of the chat part of the show has to be funny. The scenes generate the comedy. In fact, if you use up the funny on the sofa, it’s sometimes harder to get ideas to bring into scenes. Rather than grilling other people on their stories, try and bring in your experiences. After the first beat, chats can be inspired by the call-out, by previous topics, or the scenes that have gone before. Scenes: The scenes are ‘follow-me/premise-style’, which means that improvisers will only start a scene when they have an idea based on the conversation that is happening. You can do this any way you like, but here are some ways in: Mapping; putting one situation on top of another. I.e. A familiar cop scenario ‘You’re just too much of a maverick, Kelly, I’m gonna need your badge and your gun’ mapped onto a flat mate disagreement might be ‘You’re just too much of a maverick, Dave, I’m gonna need your fridge space and my towel back’. Game; a premise where the moves are laid out (or found) up top. I.e. you get angrier every time I mention food. In this form, the game is likely to be laid out in the first line or two rather than found. Character: Embody a character that was described and put them into the worst/best situation to bring out their characteristics. Emotion: Take the overwhelming emotion of the subject and put this into the worst/best scenario for it to be explored. Point of View: Use a strong point of view from the chat and set it in the best/worst scenario. Quotes: If you particularly like a line that was said, quote it directly as the initiation of your scene, or play in a world where it is super important. Questions: If you question something that was brought up within the chat; i.e. an incorrect fact or something you just don’t understand or relate to, you can play this out. Edits: Edits are the moments when we move from a chat to a scene or vice-versa. Edit from the sofa by talking. Edit from the stage by moving back to the sofa. You can also use tag-outs and tag-runs within a single scene. Tag-outs are where you replace one or more characters in the scene, therefore keeping one character from the previous scene. The idea is to add more information pertinent to what was just said or discovered and to cut back to the original scenario. To tag, tap the person(s) on the shoulder that you want to replace. Tag-runs are multiple version tag-outs where one character is kept in for 3 or more short scenes illustrating one point. A simple example from our show, is one of our improvisers on the sofa saying ‘who rings the doorbell at midnight?’ at which point we illustrated a lot of instances when that might happen. ‘Pizza?’ [tag out] ‘Hi, I live upstairs, could you keep the music down?’ [tag out] ‘Some water is seeping into my flat…’ [tag out], etc. The timing of edits is different to other shows; you are not waiting for a good edit point from the sofa, like a laugh, the end of a story or an insight, you are merely waiting for an idea. As soon as you have one, edit. No matter how rude it may seem to do it then! We can always revisit the story and there’s a lot of comedy to be had in following the inspiration. It’s also much funnier to have a sofa than chairs because it’s pretty awkward skipping onto the stage from a comfortable lounger. The energy of edits in this show is particularly important, as there is a lot of sitting and talking. Other tips: We discovered that sitting in a different seat on the sofa every time you returned was a nice way of changing up the energy. Drink beer; it makes the show feel different to a regular long form and makes you a little sillier and more confessional! The visual of people drinking on a sofa also helps transport the audience to a living room atmosphere. Remember that the audience is there! It’s sometimes quite hypnotic talking to the other 4+ people, so talk out and remember to project. Warm-ups for this style: 8 Things about me Word at a time story in a circle Tag-out scenes in a circle (keeping one of the characters each time) Anecdotes: Three of you describe (to-camera, mockumentary style) a shared-experience. Have fun with this form and thanks for reading! About the Author: Katy is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes. I’ve been lucky enough (maxed out credit cards enough) to have been in Chicago a number of times. I first went to do the Second City Intensive in 2005, then the IO Intensive in 2008, then to hang out in 2015. Since the first time, us Maydays, have brought over loads of teachers, because they are some of the best in the world. Last week we went over as a whole company for our DIY Intensive training program.

Here is a disgusting, boiled-down version of 30+ hours of improv learning for the Buzzfeed Millennial mindset. There are SO MANY exercises, insights and philosophies from all of these teachers, but this is just a taster. 1. Let’s give each other stuff we want to play - Jorin Garguilo We spent time in class literally asking one another what we like to do on stage and making one another aware of that. So you like playing animals, being picked up or getting pimped into difficult stuff? Great; tell your team and mess around with that. 2. Everything you need is already here - TJ Jagodowski I lost count of the number of times TJ would stop the scene within a few seconds because we were denying our own offers. Look at how you’re standing. What was that expression about? Did you feel that underlying tension? You seem like colleagues, no? Let’s just take a second to acknowledge every micro-offer, then we hardly need to work at all. 3. Don’t just yes, add information - Adal Rifai We’ve been learning ‘yes, and’ since day one, but actually we can be a lot more efficient. Once we get the first line, we can really go to town on detail. Take a moment to check if you are and-ing, or if you’re just yessing with a lot of words. 4. Flip-flop between things you find easy and things you find hard – Mick Napier Mick is the king of personal feedback and I learned a lot of great stuff. As a teacher, I really loved that instead of banning us from a habit, he would have us toggle between doing that thing and doing the opposite. Play fast/slow, play high/low status, initiate/react and so forth. 5. Have the conversation about physical boundaries - Rebecca Sohn I have written about Rebecca before and I think she’s an exceptional teacher. We did a lot of great physical and character work, but I was really pleased that she initiated the question of what we were all comfortable about on stage. It’s a great discussion to have with people you work with. Will you feel comfortable if I’m touching this/that part of your body on stage, if I’m kissing you, if we have a physical pile-on? Have this conversation with your group. I’ve been working with the Maydays for 12 years and this was still valuable as hell. 6. Kill, Marry, Fuck - Rich Sohn Using these basic human extremes of emotion, we played out (sometimes the same) scenes, pushing in each direction. Marry is broadly ‘negotiate’ and the others are exactly what you think they are. Really, everything boils down to this. 7. Play appropriately for the show you’re doing - Bill Arnett Bill is the Maydays’ spirit animal and we continue to learn ALL of improv from this guy. The sentiment that keeps hitting home from Bill for me is that improv is not one set of rules, it is a particular style for a particular show. Work out whether you’re playing hard premise/follow-me scenes, slow burn/relationship scenes or any particular kind of style, then put that into your rehearsals, warm-up appropriate to that show and have a director guide you as to what’s right for THAT show. 8. How to find an emotional point of view- Farrell Walsh When you get a one word suggestion, there are lots of ways to take it into a scene. Think about how you attach to ‘strawberry’ as a word; does it make you feel summery, fruity, allergic? Attach to the context of the word; how are you at a tennis match? Bored, exhilarated, lost? Is there anywhere else you’d feel that feeling? Perhaps you’d also feel lost at a supermarket like you did when you were small. Boom; there’s a feeling and a setting for your scene. 9. Show Up After a few years, it seems like the easiest thing to do in improv; get the hell on stage, but I found myself hesitating in my first Chicago show because I was playing in a 13-strong cast with veteran players. Hesitating doesn’t help anyone. Show the hell up, that’s the only way you can follow through on supporting your fellow improvisers. We’re always being told to make our fellow players look good, to serve the show; well, this is the best way of doing it. Get on stage. If you’re auditioning your idea or anyone else’s, you have already lost the battle and the moment for that idea will have passed. 10. Make room for others This is the other thing I learned from playing with the cool kids; there is always a hand reached out; we are in this together, no one will be left behind. Bring someone on who hasn’t got on stage yet, leave space for them to respond and play, treat them like a genius, artist and poet. 11. Stage Time is Everything It’s all very well learning a lot of theory about improv and reading books and quoting the teachers you’ve had, but it’s up to you to create your own philosophy and style. The only way to learn to be a successful performance improviser is to hit the stage regularly, watch a lot of shows and play with people that challenge you. About the Author: Katy is a London-based improviser who plays in Destination the improvised podcast, a whole bunch of live shows including Project2 and The Maydays and teaches improv classes. Thanks to The Annoyance, Bughouse and IO theatres for hosting shows with us, to all the incredible teachers we had, co-stars we played with and friends we made. And thank you for reading. |

Buy the Book!Enjoy my blog? Fancy buying me a cuppa to celebrate?

There are many blogs! Search here for unlisted topics or contact me.

AuthorKaty Schutte is a London-based improviser who teaches improv classes and performs shows globally. Recent Posts |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed