|

I just came back from Hamburg where I was teaching and performing for TÖRN festival. It’s difficult to be positive in the times we are living in and I was so happy to be at a festival where the theme was ‘How do we want to live?’. I was reminded that improv is of course not just entertainment, but an immediate response to our lived experience. It also gives us some tools to navigate the world and look at it with a positive spin. I’m not talking about toxic positivity where we are all inanely smiling and pretending it’s fine, but where we believe that change is possible; where we really can listen to all sides and continually question our own beliefs and actions.

Chris Mead and I took our improvised science fiction show Project2 to TÖRN in the form of Hopepunk. ‘Hopepunk’ is a subgenre of speculative fiction that is the opposite of ‘grimdark’. The term was coined by fantasy author Alexandra Rowland in 2017. It doesn’t mean being nice and avoiding conflict or setting your story in a perfect or beautiful world. Rowland gives an example; “sometimes the kindest thing you can do for someone is to stand up to a bully on their behalf, and that takes guts and rage”. Counter to ‘grimdark’ fiction (violent, amoral and cynical) such as Game of Thrones, The Witcher, Breaking Bad and The Walking Dead, hopepunk lives in narratives like Mad Max: Fury Road, Lord of the Rings, The Expanse, Saga, The Good place and Parks and Recreation. Characters fight for positive change, community and kindness. If you are feeling the darkness of the world, create ‘noblebright’ characters in your improvised fiction. Have them fight and take risks for a positive, empathetic, community outcome. And if you can, bring hopepunk into your own life, because kindness is a radical act.

78 Comments

When most people see (good) improvisation, they don’t believe that it’s made up in the moment. There will always be a cynicism that the performers have somehow scripted a whole play or comedy show then found ways to change it just enough to fit in audience suggestions and create the illusion that it’s made up on the spot. I’m always thrilled to hear this criticism because it means that we’re achieving what we want; making our shows look like they’ve been carefully edited, rehearsed and directed.

Fitness is an appropriate metaphor for improv. It’s a seemingly simple thing to run a marathon - just run 26 miles! - or to lift a heavy weight - just lift it! - but the work ahead of those achievements is huge. You’ll need to run nearly every day with increasing mileage, speed and attention to form, or lift weights and build muscle mass over a long period of time, changing your diet and putting many hours in. When we teach improvisation to new students, I’m amazed at how hard it can be for some people to have a totally normal conversation or talk nonsense in front of a small audience. The challenge is not the act itself of course, but the many things we have to cope with thinking at the same time. Am I doing it wrong? Will people think I look foolish? Why am I doing this? What will I get out of it? How does this relate to my life and my work? Kids don’t generally have this problem, and a NASA study tells us that 5-year-olds operate at 98% in the ‘genius category of imagination’, 15-year-olds at 12% and by adulthood we have fallen to 2%. Our overthinking, self-judgement and perfectionism (especially if we are socialised female) can be totally overwhelming. What then, can we do about it? Improv will help you embrace the genius that you had as a kid; that’s why so much of our work feels like being back in the playground! Everything is gamified so that important creative work doesn’t actually feel like work. We’re so amazed by the simplicity of that idea that we mistrust it, just as some audiences cannot believe that our shows are improvised. I suggest you start small and easy; take an improv workshop, then try one of our games in your next team meeting. It’s like embarking on your first couch to 5k, or taking an intro to weightlifting. Bringing actual creative thinking into your workplace or your life at large is simple. The only hard bit is forming new habits of thinking, new ways to override our adult cynicism and extending that generosity to our friends and colleagues. First published in Status Magazine.

Four years ago I started jogging. I can’t remember why. I found it incredibly difficult getting through the couch to 5K. A friend had taken up jogging at the same time I had and was quickly racking up the miles, thrilling that it was their favourite new thing. Quite soon, they were competing in half marathons, changing diet and getting super fit while I was repeating weeks just to get to my 5K. I eventually made it - mostly hating it - and once managed a 10K by promising to buy myself a literal medal. I let running slide. I’m writing this on 17th May 2021 and that’s significant in the UK because it’s the day we’re coming out of the pandemic in the most tangible way for a while. Many people have had their first if not second vaccine, theatres are opening up, friends can stay over, accommodation can open, we can meet in larger groups, some international travel is possible without quarantine and so on. Though we’re opening up at different times in the world (and some are suffering more), a lot of people are moving (back) to real world improv. Eight weeks ago, I started jogging again. We’re planning a hike in Scotland and I need to get physically ready after a year of yoga and nature walks. I expected to agonise through it like last time, but something interesting happened… I liked it. I have had a complete attitude shift. 41 year old me is much more chill. Last time, I was executing the instructions to the best of my ability. I was running as hard as I could during all the running bits and impatiently striding in the walking bits, or worrying about the next run. I was trying to be physically fit. This time, I’ve been enjoying my music, the Zombies narrative of the app and the nature around me. I’m not looking at the clock and I’m cooling down with yoga as a ‘treat’! I’ve been listening to my body instead of the commands. There’s a ‘free form’ run bit where you can choose to run or walk as much as you like. I mostly jog at a gentle pace, but I walk if I feel like I want to take a moment to catch my breath. I am doing it for my mental health. Physical benefits are a bonus. 4-years-ago-me would be pushing hard through discomfort. We’re told to push ourselves, to battle constantly, to never quit, to be the best we can be. In this new season of C25K I am being present and enjoying myself and noticing the difference in attitude between now and before. It’s not always easy to leave the house for it, but knowing I don’t have to put in a personal best when I’m on my period or go as fast as I can despite the muddy, rainy conditions is a huge relief. And you know what - now I’m running all the running bits. I have my first live gig soon. I’m not rushing into it. I gave myself some time. Friends are throwing themselves right back, but I don’t have to run a half marathon just because they are. I am listening to my body. A rehearsal Doodle has come through, but I’m asking the company what our goals, vision and expectations are before I tick the boxes and opt back in. ‘What is this and why am I doing it’ are important questions. I’m not just going to pick up where I left off. I have learned a lot and I’m much better than that. If you want to do (and are able to do) live improv (again), run at your own pace. If you’re not half-marathon person, that’s fine. You don’t even need to compete with past you. Come with a beginners mind. Enjoy everything you learned and put it gently into practice. There is no worse or better, there’s really only present and different. First published in Status Magazine.

The Improv Place asked an impossible question; given the choice of success versus mastery, what would you choose? 81% chose mastery. But what are either of those things in practice and how would you change your practice in order to strive for one or the other? Firstly, there is no singular benchmark of success for improvisation. What is it for you? Getting on television, playing big or famous live venues, getting paid for a gig, teaching, touring, playing with people you admire, getting onto a team? Whatever you think it is, your parents or friends might see it differently. I spent years working on a fringe show that got 5* reviews, but it was the two-hour shoot where I had one line on a TV commercial that had my family excited. My bank account also considered the latter more of a success. Success scares the crap out of me. I have to choose something that looks attainable in a short space of time and I create habits that drive me towards that. Once I’m successful there, I’ll look at the next thing. Or if I fail, I’ll change tack. For others, they may prefer to look at the big picture and strive for a big audacious outcome, mentally walking back through how they might get there. One Big Success. I was doing stand-up comedy in my 20s (I’m 41 now) and I was finding it hard. Good, but hard. I made a 5-year plan and measured my successes by ticking off goals as I went. These included ‘getting paid for a show’, ‘getting somewhere in a competition’ and ‘headlining’. I found myself on the other side of these goals (hooray me!) three years in and I wasn’t really that happy. I realised that stand-up - on that circuit at that time - were challenging me, but I wasn’t loving it. I was backstage while MC-ing a Funny Women show, looking at the talent around me, crushing it on stage and thinking ‘is this what I want to be doing’? Around that time I saw Arthur Smith playing in Portsmouth. I’d played the same stage. I was in my mid-late 20s and he was in his 40s or 50s. I remember thinking that if I was still doing stand-up at this venue 20 years on I wouldn’t be that happy. I imagine he was though; and he was excellent. I started taking improv ‘seriously’ at about the same time that I was embarking on a stand-up career. The Maydays were handed an award by Jimmy Carr, I was a Funny Women Finalist and both avenues were looking good. But it was by looking at my Arthur Smith future that made me feel like stand-up wasn’t the right path for me. It was panel shows and sit-coms that I wanted, not the stand-up itself. And it was the external validation in those ‘fame’ gigs that was my actual need, not the work itself. On the flip-side, I knew that if I was still playing pub improv gigs in my old age, I would be happy. That would be fulfilling enough. That was the moment where I chose mastery over success. Here I am, then, 17 years on and feeling very happy with my choices. I chose the path that I perceived to be less successful. I couldn’t see a clear route to TV or personal notoriety by choosing improv, but I did want to be really good at it. When we surveyed The Improv Place, those people that didn’t vote for mastery, voted against it because it felt too difficult, like ‘gaining’ mastery wouldn’t be doable. But ‘gaining’ mastery is ‘succeeding’ at mastery; I don’t think you can ever reach mastery in improv, not really. For me, it’s the difference between striving and attaining. When I look at success, it puts me in a mindset where I feel that I am failing. If I haven’t got to the next touchstone yet, I am actively failing. I have not yet achieved the success, my ego believes that I am a failure or at least that I could do more to succeed. Success comes with a finish line that keeps moving ahead of us. Mastery, however, means that every time I do a show and every time I rehearse, I am on the path of mastery. I am becoming more masterful. You gain mastery from failure, but you don’t get success from failure! I learn from my mistakes and I get better at my craft. The great thing about mastery is that success becomes a delightful side-effect; a lovely surprise that is an added bonus for all the work you are enjoying. When I get great job offers I am thrilled and when I don’t, I’m not worrying about them, I’m happy carrying on with my craft. We were talking in The Improv Place Office Hours yesterday about failure moments in improv scenes. The question was; how do we deal with it in the moment and not let it get us up in our heads and throw us off our game? My revelation was slightly different. I realised that it wasn’t failure that I found uncomfortable, but rejection.

When we talk about failure in improv, we’re often talking about missing information; for example, misnaming a character or making a story choice that goes against something that was said before. When we’re new to improv it can feel like blanking or doing something ‘too weird’. We play a lot of games and run exercises in class to make students ‘comfortable with failure’ to allow a larger comfort zone and tolerance of mistakes and miscommunications, to harness errors and to make them part of the tilt or fabric of the reality. I’ve been doing this a long time, but clangers can still feel bad; after all, the Patriarchy says I should only do things if I’m perfect and indeed if I’m better than the boys. I’m also aware that failures can be the exciting bit, the bit where the magic happens. At the point I mess up, the show gets more interesting. It’s stopped following the train tracks, it’s not prescribed or predictable. My failure has created a place where someone (including me) can take this new information and steer the scene according to a new truth. It’s the place where improvisation justifies itself as an art form. We all know that failure is inevitable in any creative enterprise. The more we fail in fact, the better an outcome we get; iterations give us solutions. So why does it sometimes feel great and sometimes feel awful? I think that’s all in the reaction to the moment. Firstly, there’s our own reaction; if we broadcast that it’s a mistake with our facial expression, body language or speech, it’s going to be taken as one. That’s commitment 101. Sell every line, every idea like they are excellent. Secondly there is the moment that comes after. Our mistakes can either be embraced, or met with rejection. “If you hit a wrong note, it's the next note that you play that determines if it's good or bad." - Miles Davis I personally never loved games or scenes where students are jokingly told ‘that was shit, get off’ or where there’s an elimination or punishment aspect (unless it’s self-policed, then I’m okay with it). Particularly for women, perfectionism is so strongly baked into us by society that to mess up a silly warm up game can feel like the end of the world if we are being shamed for it. If the failure is celebrated and embraced as an achievement, that puts me in a much better headspace for risk taking. If the whole jazz band suddenly stop playing and look at you like you’re dogshit, that’s how rejection feels. As Brené Brown tells us, it’s a human need to belong, not just to fit in. I’ve certainly experienced my failures being both embraced and rejected in improvisation. I was playing in a teacher show at an (amazing) improv festival. It was getting crazy and I came in with a weird chef character that was a big choice; I was hoping to solve a problem in the scene. One of the other players said “And I have to yes-and that?”. It got a big laugh. It was certainly a way of releasing the crazy tension in the scene. For me - I felt awful and didn’t really make it back on the stage much for the rest of the show. I felt shamed and exposed; I had been told by a well-known improviser and in front of my students and community that my offer (and therefore my improv) was terrible. I don’t bear the improviser any malice, but it is a useful illustration of how rejection influences play. In contrast, I have a very fond memory of playing in The Improvised Star Trek Podcast that ran for 5+ years and shared some of the cast of the more famous The Magic Tavern Podcast. I was worried about remembering all the names, titles and circumstances of years of backstory. I decided to play a lowly cleaner on the ship so that I wouldn’t have to ‘know’ all of these facts as my character. Rather than let me play in the background for the whole show, the other characters all decided to change jobs and to promote me to captain. Every offer I made felt golden and I had the time of my life. When the offers you receive are fun and generous, all you want to do is be generous back! I wonder if ‘get off, you’re shit’ rejection is a British Old Boys’ Club embracing of toxic masculinity. It is certainly reflected in some Clown training too. See this great article on Via Negativa. Casual bullying and name-calling was always part of the fabric of my education in school and symptomatic of a society that ranks individuals, breeding a culture that believed tearing another down was the way to rise to the top (whatever the top fucking means). Perhaps the reason I was so thrilled to learn IO Chicago’s ensemble style was because I wanted to fail with joy and not rejection. To belong, not to filter my behaviour to fit in, to feel like every offer was a gift, not to be judged, but to be embraced. How do we cultivate a joy over rejection model of improvisation? Build up trust and be kind before every rehearsal, workshop and show. Make sure that you have exchanged boundaries and foundries (things that fire you up with joy) and warmed up or at least gotten on the same page. People are less likely to throw you under the bus if they trust that you have their back and if they like you. If you felt rejected or shamed in a show, talk to the person who made the rejection move. They were likely in a fear place and telling them how you felt might change their future choices. Remember not to shame them for their choice, just tell them the story you’re telling yourself about that moment. This is how we grow understanding instead of resentment. Ideally you’ll be playing with a group that knows how to play that sweet next note, but if not, you need to support your own failure, even if no one else on stage does. If the rest of the band are looking at you like dogshit, play your own kick-ass solo. Repeat the thing you did until it’s a running joke, or elegantly justify it being there. If you get a name wrong once, be a character who gets names wrong. If you made a story move that didn’t make sense, hold onto it and fold it into a clever plot twist at the end. The writer put it there, so there must be a reason. Remember how you can bring the joy for other people; make their mistakes feel golden. Try not shame others by throwing them under the bus. Justify those tilts so that they are the one note that makes the song. We have an art form whose tenets boast comfort with failure. Are any of us comfortable with this failure?

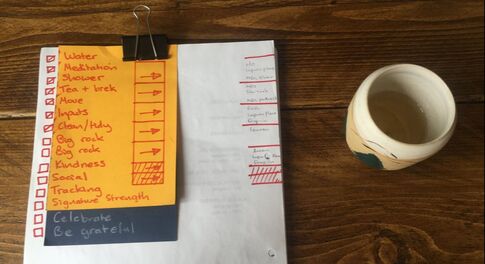

The history of pure improvisation on TV and film is almost non-existent. We have game shows and panel shows with producers live-directing the cast and much written stand-up material stuffed in where possible. Anything good that comes out of improvisation on TV or film is because of the edit. Our best examples are assisted by heavily structured storylines with alternate takes, edited into their best possible shape afterwards (e.g. Paul Feig). We have characters immersing themselves in a world where a puppet-master introduces elements for them to react off of (e.g. Mike Leigh). We have real life and emulated real life where people are aware of the cameras (documentaries/reality shows and the mockumentary style made famous by Christopher Guest). But when something is edited, it is not live improvisation. It’s writing. So why are we trying so hard to make improvisation work online – and can it? In these lockdown times, improvisers have thrown themselves into different camps. There are those who have switched off and avoided; feeling fear or even a sort of betrayal in learning, teaching or performing online. Then there are those whose identities are challenged by not being able to improvise live: their solution is to double-down and reinvent, imagining themselves noble where perhaps the reality is anxiety or a necessary desperation for income. I have visited both camps. For the first few weeks I felt a huge sense of overwhelm, that I should, that I was a bad person for not, that I was doing it anyway and was that unfair because I didn’t believe in it? After the first flush, the sorting hat of post-live improv gave us clearer factions, spilled out around the community, some preaching, some struggling. Unsurprisingly, it was the strong-willed A-type coming to the fore. I will teach you how to do this new thing (that I am also just learning myself). Those comfortable with the technology are leading the blind like gurus, fake-it-till-you-make-it-ing and saying it is a kindness. I’m a science fiction fan, so this all seems very familiar to me. I’ve lived my life with a few extra food cans in a corner cupboard; on every flight, I say Thank the Gods to myself as I imagine telling my grandchildren about the Sky Birds that used to take us to distant lands. None of this feels like a surprise, though there are very few of us – including me - who planned ahead to a time when we can’t play an actual physical improv game with actual physical contact. In the beginning, then, we used online improv for sanity. In our Maydays drop-ins, one of our check points for a class was to reassure everyone that they may feel strange or sad and that’s okay. Our only connection as a species was found online and therefore any improv, any conversation or silly game was enough, it kept the Black Dog from the door. Everyone is in a different state of course, this is harder for some than others for reasons we all understand. Normality was the next phase, finding something that was routine. Waiting for your favourite improv school to put on a drop-in class so that you can go along like it’s a normal Tuesday. Then a jam night or – Blessed Be! – a course. I find myself going into a week with four nights of teaching, a show or two and a podcast recording. Apart from living through a pandemic, life is familiar. But what happened to the Dark Night of the Soul? What about that bit where I cried with my whole body at the breakfast table in front of my husband, wondering how I would be able to stay independent and who I even was if I wasn’t an artist and a teacher. Wasn’t there a reason for that? Are we just normalising our regular schtick and expecting it to work in this new medium? We smile and congratulate ourselves for doing a show or class in ‘difficult circumstances’ with all the compromises that come with two dimensions, an invisible, inaudible audience and semi-pro equipment, using an art form that hasn’t worked longform on screen… ever? I worry that we’re doing it for us and not for an audience (and perhaps that’s fine). I’ve played in a couple of passable shows and a delightful one or two, but I don’t know what they were like for the audiences. I’ve not watched them back and I haven’t been able to sit through a single full show made by any improv group. Sometimes I’ll watch the first 5-10 minutes and think ‘well done, that basically works’ and be able to take a trick or too back to the cave. Lots of my colleagues and friends have ideas (and blogs) about what works or what doesn’t work, what is or isn’t a good show or form or framing or set-up, but not that many people are asking why. Longevity is the thing that most of us don’t seem to be comfortable looking at. Yes – we have no deadline and that’s the hardest thing of all. Perhaps if we knew it was six weeks; we’d all try and take an actual break or just tidy the house and read, but because we don’t know how sustainable we have to be or how long our money will last, we are in the dark. What happens after? For my part, I’ve been teaching writing, which I don’t think loses anything from being online. This isn’t a sales pitch, because they all sold out. It’s a humble-brag, then; but one that’s here to underline the point. After… all this; I’ll still be able to do that course and it will be a good one and people will still join from all over the world. But that’s not improv. Will anyone still be going to online drop-ins after the fact? No. It may be a tool for teams spread around the world, it can be an in for people who simply cannot join a live class, but I don’t think it will sustain. My open question, then is how are we spending our time and why are we doing it that way? Let’s think of things that will last; what improv show would be better online than on stage. Can we admit that podcasting* has already totally nailed it for years? What can we do with screens and text and screen-sharing that we can’t do on stage? I don’t know, I’m an amoeba right now, but I’m pretty sure no one has cracked it because Netflix. I am the biggest fan of good improv, but if it’s a wrinkly green screen and that fucking space virtual background, I’m going to watch Better Call Saul. What I have enjoyed are shows that take mine and your suggestions the moment we tune in, absentmindedly, half way through; I can hang out for five minutes before I’m distracted by something else. Shows that ask us to buy a ticket (from a finite number of tickets) because when we invest any amount of money, we put the show in our diaries and we stay for the duration so that our money went somewhere. Shows that then delete the show. Give me FOMO. Make me feel like I missed out and I must be there next time. The advantages are; where we are in the world doesn’t matter. I can play with and teach anyone from anywhere and that’s awesome, even if it is at 3am. There is a limit to who can go to improv festivals because they’re expensive to attend, they may not be accessible to everyone and there are people who are committed to family holidays. This crisis levels the playing field a bit. There is a coming together – we are sharing information as we discover it. All the Zoom calls between improv practitioners, the lists of Facebook interrogations into the situation and the many blogs. Let’s move from sanity to longevity. *My friend Lloydie's thoughts in a great blog on podcasting in these times.  I’ve been blogging about improvisation for a long time now. This blog is not about improvisation. I have anxiety and depression. I don’t experience depression all the time, but the more I understand anxiety, the more I understand that I’ve had it for pretty much all of my life. I’ve read a lot about anxiety and depression (articles and books), I’ve been in therapy and I’ve been close to people who have contemplated taking their own lives. I now have a system to help me enjoy life. It’s not foolproof and it’s pretty personal. I shared a picture of it on Instagram and I got a lot of messages and questions about it, so here’s the system and the explanation. Take or leave it. It’s a collection of the evidenced self-help I’ve found and successfully tested for me personally. Don’t Do All of This at Once: Because of my anxiety, I want to fix stuff immediately, do all my homework at once and tick all of the boxes. If I don’t, I get bored really quickly (ADHD?) but I learned from wellbeing that you can’t do it all at once. You can’t put all of the habits successfully into practice right now and be successful for more than a short period. This isn’t a crash diet, it’s a life choice. Put one in per week, or one until it’s stuck and then add another. Take or leave them according to what works for you. When you fall off the wagon and ditch all of these things, forgive yourself and just start again. Accountability: For me there are some things I like to do secretly. When I started jogging a few years ago, I didn’t tell anyone about it – not even my husband – until I could run continually for 30 minutes. My husband twigged of course when I kept leaving the house early in my gym clothes and coming back muddy. My accountability for that was to put an event in my diary and/or tick a box on a postcard when I’d done it. Nowadays I’m happier to be held accountable by friends. There are various apps and systems I mention below where I have a buddy and we check in with one another. Today, for example, I checked in with my friend Eva because we are both trying to write 1000 words a day this week. Routine: Routine is great for mental stability. It’s in all the Amazing Habits for Geniuses type books. I’m self-employed and my routine is very weird and up in the air. I can be travelling or coaching early in the morning and teaching public classes or doing shows late into the night. How? As you can see from the image, I have a piece of card with a list of categories on. Each morning, I move the card along my pad and write out boxes which I tick off throughout the day. On the right-hand side, I have a hand-drawn version of my diary for the week. It only has bullet-pointed events for the days and no times listed. It means that I have an idea of the days ahead without having to look at my phone or computer (where my actual diary is kept). There’s very little space on there - only two to three things fit – so it’s very easy to see when I’ve taken too much on, or when I have neglected to take a day off. BOX TIME: Here we go, then. A little bit about what each of the boxes mean. Water: When you wake up, drink a glass of water. I learned this from the Fabulous app. It sounds so simple, but it’s amazing how long it took me to get this into my routine. I like it, it wakes me up. You can do hot water and lemon, but hot or cold is good and it starts to wake your body up. Having something other than your computer or phone for the first few items in this list is also great for your brain. Meditation: I’ve been using Headspace for years. I tried it off and on for a long time. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve started paying for it and only in the last year that I’ve actually been able to stick to a daily practice. At first, I found that I wasn’t doing it for the sake of meditation, I would get out of bed at night to do it if I’d forgotten, just to get the tick for having meditated that day. Now I do it because I want to meditate, not because I’m married to the every-day streak. Sure, I’ll be annoyed if I break 125 days in a row, but that isn’t at the heart of why I’m doing it now. I’m feeling the benefits for real. Also, I’m still shit at meditating. My mind is all over the place for most of each meditation, but it’s worth it for those rare few breaths when I’m not rolodexing thoughts about everything else. Shower: I don’t really know why this is on my list. I always shower daily. I guess it’s because it fits in with a morning routine and it’s satisfying to tick it off. Historically, I suppose, there are days when - even though I do shower - it can feel like a chore, so it’s important to keep showing up in this simple way. Tea and (healthy) breakfast: It doesn’t take any real effort for me to eat a healthy breakfast. I love brek. I love eggs, I love porridge, I love bircher. If I’m busy or getting up very early, I’ll make bircher the night before so I don’t end up getting a pastry breakfast on the way somewhere. That’s the change, making sure there’s a backup plan if busyness is going to get in the way. Tea is a ritual I love. I really do savour my tea. I make loose leaf tea in a pot and it tastes really good. I have a handmade cup from my friend Audra at Imaginary Attic Ceramics and it feels good in my hand. If I’m travelling in the morning, I’ll make a thermos full of beautiful sencha, oolong or popcorn tea. Move: This is a my purposely loose term. I learned to jog on a regular basis via Couch to 5K, then graduated to Zombies, Run! which is a ridiculously fun immersive storytelling running game. Then I switched it out for long walks training for a three-month trek that ruined my right knee enough that walking was painful for months. I still hope to get back there but physio is incredibly boring. When will they gamify it?! I have, however got on the Yoga with Adriene bandwagon. She is excellent and very funny. I’ve taken maybe two or three live yoga classes in my life and only enjoyed the last one which was up an Austrian mountain for a holiday commercial. I do Adriene’s 30 Days of Yoga videos, but I certainly can’t do it every day. Instead it will take me a few months to do 30 days of yoga. The thing is – that’s okay! On the days I don’t do that for whatever reason I walk for 20 minutes or more. The other reason this box says ‘move’ is because sometimes – when I’m depressed - just getting out of bed or going to my desk can be difficult. Move, therefore can have a different quality depending on what is happening physically or mentally for me on any given day. I must to be honest with myself, though; if I just got out of bed on a day when I am more than capable of doing yoga, then I don’t get to tick the box. I often give myself a free pass at weekends or on days off. The days when I really try hard to move (exercise) are the ones where I am up at 6am and/or working 12+ hours. It’s perhaps counter-intuitive, but on a day off I like to relax and on a working day I like to be fit to rock. Inputs: This (and Big Rocks, coming up) are from Graham Alcott’s book How to be a Productivity Ninja. Inputs just means checking all the places where you get messages. I try really hard not to check all the time, but I’m not disciplined enough to stay off my networks save for two time slots a day. (I have taken Facebook and Twitter off my phone which meant that I completely forgot about Twitter and that I check Facebook rarely.) I respond to quick emails and file others appropriately for a dedicated session. See Graham’s book for the system stuff. I’ll go through my Slack channels, WhatsApp and socials and get all that to zero. Clean and Tidy: I read Marie Kondo many years ago and found her method excellent (even if she doesn’t like pyjamas). It wasn’t the decluttering so much that stuck with me (because really, you only do that once) but the mindful attention to folding and storing things. Clean and Tidy therefore is listed to remind me to be present whenever I am cleaning and tidying. It shouldn’t just be a rushed chore between important things, but a moment to relax and savour. Big Rock: I have this check box twice on my list. At the beginning of my day, I write down the things on my to-do list that I am putting off the most. Perhaps it’s a big job, or perhaps it’s just something I think I won’t enjoy. Instead of having those things hanging over me, I’ll get them done as soon as I can so that I won’t be worrying about them all day. If it’s a really big task, I’ll allow myself to just do 20 minutes of it (which gets me started and probably I’ll go much longer). Kindness: I added kindness and most of the following points to my list after doing a Yale course on Coursera entitled The Science of Wellbeing which evidenced things that are proven to increase happiness levels. Kindness is a tough one for me. I’m still discovering things that fit here. It can be offering my expertise for free on something, giving money to a cause, offering my seat on public transport or anything really where I feel like I’ve been kind. Today, for example I had a new desk delivered, so I offered my old one up for free and a lady from my block of flats was grateful to take it. Social: This is also against-type for me. I can live behind a veil of work very easily. I had to make a deal with most of my close friends that at least sometimes we must just chat about life stuff and not a bunch of cool projects we do or want to do together. This box can be ticked by a non-agenda lunch with a friend, but it can also be ticked by a nice chat with a stranger. I’m someone who naturally goes to self-checkout even if there’s a cashier free, but studies show that that makes us less happy, so now I go and talk to the human when I can. I’ve even had a few chats on the Tube which is unheard of and definitely out of my comfort zone. You’d be surprised though, it’s pretty great. Tracking (Celebrate and Be Grateful): This is really the same as Celebrate and Be Grateful which are also tick boxes on my list. Every night I write a short list of things that I am celebrating or grateful for on a square of coloured paper which I put into a mason jar on my desk. They don’t have to be big things. At the end of the year, I’ll maybe dip in and read them. Taking the time to reflect on positives increases our happiness levels. Signature Strength: I took a test online (https://www.viacharacter.org/) which showed me what my signature strengths are. In order to tick this box, I need to do something which comes under one or more of my top seven strengths: Curiosity, Creativity, Perspective (wise counsel to others), Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence, Leadership, Love of Learning and Bravery. Examples that fit mine include taking a new class, knitting, reading a book, teaching improv, being in the countryside, performing or writing. I hope at least some of this is useful for you. Let me know how you get on and do share your own habits that help you enjoy each day.  I’m taking a Science of Well-Being course online with Yale. Last night I did a fabulous show with The Maydays at IMPRO Amsterdam. We got a standing ovation and were called back on stage to bow again. I had loads of compliments in the bar and yet, all I wanted to do was go back to my AirB&B and feel disappointed with myself. So what happened? Well, according to my Science of Well-Being course, my salient reference points were kicking me in the butt. Looking at the happiness levels of Olympic silver medalists next to bronze medalists, bronze medalists are often happier. The silver medalist is kind of bummed that they just missed out on gold and the bronze medalist is excited to be placed. We had a technical issue in the show that meant I couldn’t hear our musical director from on stage. I pride myself on being good at making up songs and yet I couldn’t hear the rhythm or the pitch of what Joe was playing. Even though we sang less songs because of it and the story and other aspects of the show were really cool, I went away feeling like a disappointed silver medalist. I knew that if the music on stage had been audible I would have been really pleased with the show. I could have been better; I was just shy of gold. In contrast I did a brand new show with my friend Ed the night before. We’d only ever done a handful of 10-20 minute shows previously and in the last one we did we discovered a lot of things that needed work. Tuesday’s show would be 45 minutes long and have an audience of some of the world’s leading improvisers. I was nervous all day. Doing it brilliantly seemed like an outside chance. We had spent time with an intimacy coach and practised physical theatre/dance lifts and holds. We talked about the difference between a short show and our longer spot. On the night: we nailed it. I couldn’t sleep because I was so happy with how it went. It probably wasn’t any better in comparison to the Maydays show the following night. My salient reference points for both the shows were different, so even though the shows and my performances in those shows were likely of similar competency, I was thrilled with one and sad about the other. The data isn’t there for improv, but I do wonder if every time we do a particular show, we move our bar for what we imagine the quality of show would need to be to make us happy. One study shows that whatever our financial income is, we always believe that the income we need to be happy is higher than we are making now. For every dollar your income goes up, your ‘required income’ goes up 1.4 dollars! Being present and being content with a show no matter what happened and how good it was is the lesson. It might take a lifetime, but I’m striving for it. Medvec et al. (1995). When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 603–610. Our minds don’t think in terms of absolutes; our minds judge to relative reference points. Lyubomirsky (2007). The How of Happiness: A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want. New York, NY: Penguin Books. Page 44. This book tells us salary goals rise as salary rises  I’m an improv teacher, but from December to March, I took three months off to walk the South Island of New Zealand. Part of my job is helping people push past their comfort zones to find the absolute joy on the other side. I could have just sat there and told my students - from my comfortable safety zone - that it’s fine, get on with it, but it’s always good to walk the talk. Literally. Firstly, it wasn’t just a walk, it was tramping, which is a long walk with a heavy backpack across difficult terrain. We climbed mountains (sometimes several in a day), we crossed big scary rivers hoping the water wouldn’t sweep us away and we met all types of weather. We were frozen, drenched, sunburned, bruised, injured and bitten in a cycle of adrenaline and despair. It might be a bit more physically challenging than improv (even more than an improvathon) but tramping and improv have a lot in common. Here are some of the things I learned and re-learned about tramping and improv. 1. Getting ahead of yourself mentally makes you fall over now. The first month or two at least had us walking on very difficult terrain. We needed to pay attention to every step so that we didn’t fall and hurt ourselves. When we did try and plan ahead to dinner, or think about life in London, one of us would inevitably fall over. Our attention was split and we were punished for leaving the moment: happily, never during a river crossing or sidling by a drop. It’s the same as an improv scene. If you’re thinking about your next move, or a future scene, it’s much harder to listen to your fellow player. You’re falling on your listening ass every time. Susan Messing put it perfectly “If you’re up in your head, you’re not here improvising with me”. 2. Push past your fears. Moving past your comfort zone expands it for the future. I drove a car when I went to sixth form college and hadn’t driven since. The places I lived didn’t really demand one and I gradually built up a fear of driving because it had been so long since I’d done it. I took a couple of refresher lessons in London just to pretend to be prepared, but I knew I wasn’t going to drive. I injured my knee badly enough that even with three types of painkiller and a knee support, I couldn’t walk the next stretch of the hike. Accommodations – even hostels - get expensive fast, so we were left with one option. I had to drive. I stressed about how big my rental car was, about the fact that I was new to driving an automatic and that I’d never driven on New Zealand roads. Eventually though, it came to that moment. I went to get the car on my own because I didn’t want my husband to see my fear. I drove the car five minutes to the supermarket where he was picking up our resupply. I parked. I was SO excited about what I’d achieved. I ran to him, screaming with excitement and jumped into his arms. A couple walked past and commented, “how long since you last saw one-another?”, I replied “about an hour!” I drove one of the top-ten driving routes in the world. I felt like a Goddess. I thought about my newfound freedom, how my fear had held me back so much from a wonderful new world. It’s impossible to know what it will be like on the other side of your fear, but I can promise you that it will be much, much better than the safety of the world you already know. Does going on stage scare the crap out of you? If you opt out, how the hell will you know what you could have won? Say you do the worst show ever and all your friends hated it. The next big scary thing you contemplate won’t be nearly as scary and the likelihood is that you’ll love it. 3. You can climb the mountain; it just might take ages. I cried. I’m not much of a crier in everyday life, but I stopped counting how many times I wanted to sit down and cry and have someone chopper me out of the outback. The mountains were steep and everything hurt. There weren’t many paths, just orange triangles nailed to trees and rocks. We were walking for up to thirteen hours a day because sometimes that’s how far apart huts or camping spots were. I was only able to keep going sometimes because I knew there was no way out. If, six days into a twelve-day section, you decide it’s not for you; tough. It’s six days in and six days to get out. The thing is, you can take your time. Sure, you’ll have to take more heavy food if you’re going more slowly, but you can totally do that. Pace yourself in scenes. It may seem hard, but you just need to take it slow. Listen to your environment, your buddy and see what absolute beauty is all around you. You’ll get there. AND you have a chopper in the form of an edit, so, lucky you. 4. Hike your own hike. It’s okay if someone is faster and fitter than you, you don’t have to pack the same food or kit or be on the same schedule as other people. You have to make your own decisions. Ultimately, it’s your own life you’re risking when you cross that river in those boots, take one less day of food, or a colder, lighter sleeping mat. In improv, you need to listen, respond and build, but you don’t have to play fast if you don’t want to and you don’t have to make cancer jokes even if your scene partner does. Improv your own Improv. 5. Stop talking about hiking all the time. I heard so many people talking about how many ‘k’s they’d smashed in blah blah time and how light their [brand] pack was. Oddly, the more people talked about how far they’d walked, the less I cared. Improv is interesting because it’s the truth on stage. Improv itself is fake and if you’re talking fake improv offstage, that’s not as interesting. Not all the time at least. Sure we like to geek out sometimes and I like talking about improv too, but there’s a point when it gets in the way of real connection. Talk to real people about them, about you. How many times have you been to an improv show or festival and known all about someone’s training or style and nothing about them as a person? 6. Get your feet wet. One night we stayed in a hut and a family joined us. They had two young children with them. The parents were both outdoors experts who led training and expeditions for older kids. Even though we were near the end of our journey, I asked if they had any sage advice. The father told me that he would always make all the kids stand in the first stream they got to. He made them get their boots, socks and feet wet right at the beginning so that they weren’t tempted to boulder-hop. Boulder-hopping is a pretty dangerous way to cross a river (I know; I fell in when I was trying to keep my boots dry. Boy did I feel like an idiot. A very wet one.) Get your improv feet wet. Get on stage early in the show, make a bold, stupid move. Now you’re committed and you won’t be scared of making other sock and boot-wetting moves for the rest of the show. 7. Stretch. You don’t want to get an injury. It’s also good to warm up your mind and connect with your chums. 8. Adapt to the terrain. Sometimes you’ll look at the map and make a guess about how long it’s going to take you to get somewhere. Sometimes you’re faster and sometimes you’re slower. You can make a guess with your map, but you need to adapt to the terrain. It can be a Martian boulder field, a swamp, a track, a hillside scramble, a meadow or scree. You don’t know what’s around the corner and you have to travel according to what’s underfoot. Running through a bog is near impossible and crossing a river in flood can be fatal. If this scene is a mapping scene, play that, if it’s slow burn, do that. Double-down on what’s already happening and don’t try to force something else. Go at the pace this terrain sets for you. There’s no use forcing a style or technique where it doesn’t belong. 9. Pack everything; but don’t over-pack. There were so many things I wanted to pack and didn’t and maybe one thing I wish I’d brought. I did a lot of research before I went. If I’m going on an eight-day section I’m not going to take more than eight days of food (and a few emergency rations). I’d be a lot more tired and my pace would slow. You only need to think about tonight’s show. What tools do you need for this style, this technique, this genre? Leave everything else at the door. You don’t have to show this audience everything you can do, just like I don’t need to carry three lip balms and a third t-shirt up a mountain. 10. Do it for you, not for the Instas. Perhaps you saw the article and picture about the queue at the top of Mount Everest? The more we do things because we think other people will be impressed by them, the less self-worth we’re getting. I am proud and excited that I went on this journey, but I didn’t take as many pictures as I could have. I didn’t stop at each magical moment, each incredible bird or view or campsite and record it for everyone else. I took a little bit for my friends and followers and let the rest be for me and my husband. If you’re doing improv because you need people to tell you how good you are, that’s not going to solve you at a deeper level. Make sure your contentment doesn’t come from kudos or a good or bad show. I’ve said it before; you are not your show. Do your best and sometimes you’ll get a great one, but don’t celebrate or commiserate too darn hard. 11. When your wheel falls off, make sure you drive again soon. You know that driving I was talking about? I was going at 100kph and the front wheel bounced off the car. I did some great stunt-breaking and we were totally fine (apart from a bunch of waiting around and frustrating phone calls). In fact, a group of people immediately pulled over and put the spare wheel on the car and were more than kind. I hadn’t driven for maybe twenty years and this happened!? We picked up another hire car the same afternoon and I kept driving. A day or so later, I wasn’t even thinking about mechanical failures or horrific crashes any more. If you have a bad show or a difficult rehearsal, you just need to get back out there. (Unless of course it’s a bigger issue that needs resolving.) We have ups and downs in our art form and it’s normal. Go drive to Glenorchy from Queenstown and have a beautiful time. 12. Use your poles Before I went I thought hard about whether I needed walking poles. Different people have opinions on both sides. We did a few shorter walks beforehand though and I knew they’d come in handy. It turns out I wanted to use them the whole time. They spread the effort through my body a little more so there was less strain in any one place, I could check river and mud depth with them, I could use them to stabilise jumps, scrambles and other awkward moves. Some hikers even used them as part of their tents. Any thoughts I had about looking like a dick were completely irrelevant in the outback. I definitely looked like a dick, but I helped my body some and avoided death or injury a few times because of them. You may think that because you’ve taken a lot of classes, you’ve transcended the rules. I often see experienced players deny or reframe or make any other number of rule-breaking actions. The thing with rules is that they’re there as an option, as stability, to feel your way along. When you don’t need them, you can pop them back on your pack. 13. Hang your food or there’ll be a possum party Work out your own metaphor for that one. The other things I learned on this journey were obvious, so obvious that you can’t even hear them when I say them to you now. Time off makes your art better, people are more important than work, nature is beautiful and bodies heal. We often state how long we’ve been doing improvisation for in years as it’s a simple way of summing up our ability, but it’s pretty easy to tell how much improv someone has done or what level they are at in the first warm up game.

Brand new: Visibly worried about getting the game wrong, apologising facially or out loud. Telling other people off when they messed up the rules. Taking ages to pass a clap around. Laughing quite a lot as they play, part fear and part exhilaration. Some improv: Broadcasting that they have done this game before. “Ah yes” or checking in with the teacher/coach about the version they know, ‘helping’ others get the exercise when they didn’t ask. Intermediate: Playing the game to the best of their ability and not worrying too much if they get it wrong. Playing probably as fast/well as they can, but right on the edge because they know nothing bad happens if they miss a clap or drop the game ball. Experienced: They can already play this game, or if they haven’t they’re quick to understand the aim and the rules. They are keen to have a go, not have it explained loads. Pro: As with intermediate and experienced, but with the added extra that when they or someone else messes up, they automatically make it part of the game. They thoroughly enjoy the mess up and the fact that they’re being challenged. It takes a while for beginners to dial down the huge part of themselves that is worrying about how they look when they get stuff ‘wrong’ in improvisation. After that stage, they have gotten used to being observed, but they miss obvious things in scenes like being named, where they are or what the relationship is. Once that’s nailed down (and it can take years) the next stage is subtext; what’s going on beneath the words, plus a myriad of game and pattern moves. After all that, pros are bringing their own selves to the stage, raw and truthful, confident in silence, 100% leaning into any offer from their partner without auditioning that idea and also having a ball. |

Buy the Book!Enjoy my blog? Fancy buying me a cuppa to celebrate?

There are many blogs! Search here for unlisted topics or contact me.

AuthorKaty Schutte is a London-based improviser who teaches improv classes and performs shows globally. Recent Posts |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed